The Meaning of Flight:

This is the title of a poem by the Anglo-Welsh poet Christopher Meredith. The poem itself is about finding a dead swallow and the meanings he took from this experience but it was the title that set me thinking about how flight, in all its forms, is movement and transition. It is the leap of a fledgling from the nest, the restless search for something beyond the horizon, the escape, the ambition, the act of being carried, flight from is always also flight to. And these thoughts inevitably formed themselves into an idea of a painting.

In my painting, these ideas found their way into colour and form. Some lines held fluidity, fading into soft edges, like wind shaping invisible trails. Others were decisive, sharp, intentional. I let them intersect, cross each other’s paths, sometimes harmonizing, sometimes clashing. The act of creating became a reflection of flight itself—an unfolding motion, an unexpected turn, a balance between control and surrender. Because flight is not just about moving through space—it is about connection, about the invisible forces that pull, push, and intertwine. It is not simply about arriving but about the rhythm of departure and return, of detours, of the silent knowledge that every path, however solitary it seems – a lone bird against the wind – is tethered to something else; carries echoes of others, unseen influences, currents that shape its course.

Looking at the finished piece, the lines seemed to shift and breathe, weaving in and out of each other like flight paths crossing in the sky. Nothing moved, of course—the brushstrokes were fixed, the paint had dried—but the sensation remained. I had not simply painted flight—I had painted the way it binds everything together, the way it shapes narratives beyond our own. The lines did not merely move; they conversed. And in that conversation, they carried meaning beyond motion. Flight is never singular; it is always a conversation. Each line carried its own trajectory, some sweeping in arcs like the passage of migrating birds, others cutting sharply across space like the contrails of aircraft. But where one journey met another, a new dialogue emerged—a silent exchange of forces, an interplay of paths, sometimes converging, sometimes diverging.

Migration is deeply woven into the fabric of human history—it is not an anomaly, but a constant, a rhythm as natural as the movement of birds across the sky. For millennia, people have sought new horizons, fleeing danger, pursuing opportunity, following the invisible currents of necessity and hope. And yet, despite its universality, migration is often met with resistance, as if movement itself were a disruption rather than a continuation of the human story.

But what is migration if not connection? Every journey brings cultures into dialogue, ideas into exchange, traditions into new contexts. The interconnection of lines of flight—the paths of people crossing borders, settling, adapting—has shaped civilizations, fueled innovation, and enriched societies in ways we scarcely acknowledge. Without migration, languages would not evolve, cuisines would not blend, music would not resonate across continents. To reject migration is to reject the very forces that have made the world what it is. It is not only an act of movement but of transformation, of growth, of weaving disparate threads into something new and shared. And in that interweaving, humanity finds its fullest expression.

A Day Out of Time

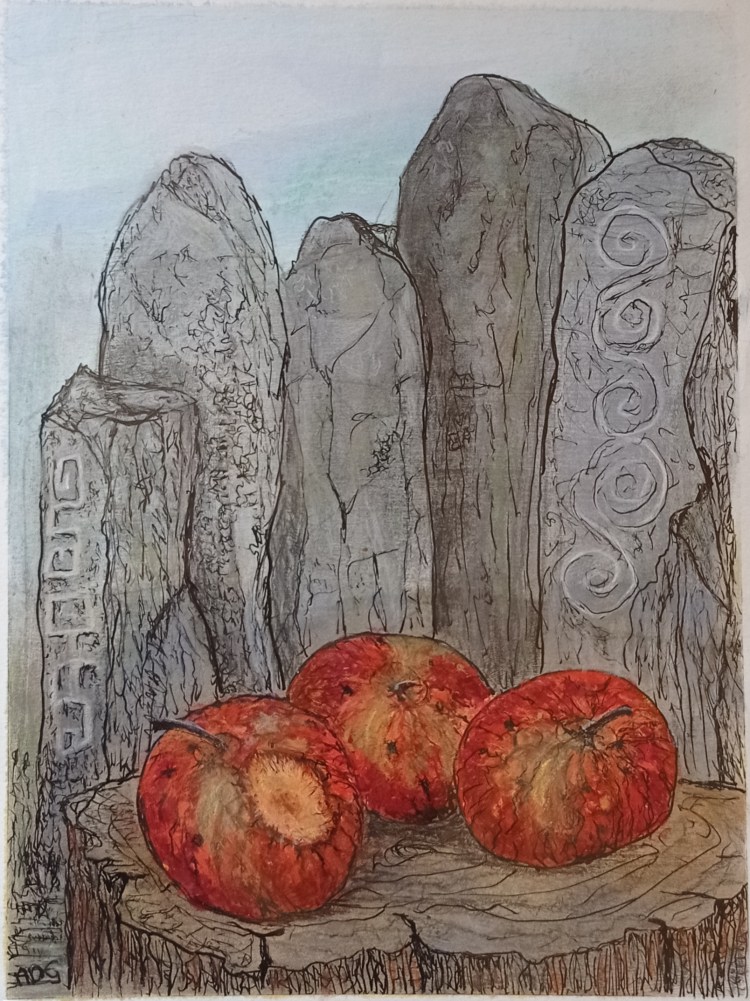

The alignments at Carnac are immense. Their serried ranks stride across the Breton landscape with a careless majesty that takes time and energy to absorb. Beyond knowing and comprehension, they are magnificent in and of themselves. We study, extrapolate and make plausible hypotheses about the alignments’ original meaning and purpose. Since no one involved published an artist’s statement or a funding proposal about the construction, we don’t know and probably never will. I like that.

To me their original purpose matters less than what they mean to us now. What we look at is not what the builders saw physically or emotionally. Physically the stones have weathered into new forms over the millennia. Emotionally we have no entry point into their world view. We do not share their ‘habitus’. We perceive and react to them from a radically different worldview to that of the people who brought and placed the stones.

So each of us relates to the stones in our own way. Each person takes from them what they need or want. Every time we look at a painting or a statue, listen to a particular piece of music or read a familiar book our response is conditioned by our own current mental attitude and mood. We see something new or we like something more, or less, or we have a different understanding.

My response was to see how time and natural forces have produced art in the stones. The sculptural forms and subtle colours of rock and lichen. The play of light and shade.

While I spent the day immersed in sketching the shapes and forms of stones My partner spent his studying the small intricacies of life. Filming the crickets, moths and grasshoppers; the way the stems of the grasses stirred in the breeze and cast shadows on the stones. A bumble bee feeding on a pine cone. Wasps gorging themselves on the fallen apples.

I saw several apples had fallen on the stones themselves and was struck by the contrast their intense red colour made with the soft grey of the stone. The wrinkled skin of the apples and the blotches of brown decay that had started to mark them chimed with the rough and weathered surfaces of the stones and the way they are blotched by lichens and moss that mark the process of slow decay.

I picked up a couple of the apples and, as I did so, I remembered childhood days spent roaming the hedgerows gathering apples and blackberries for the autumn ritual of jam-making. Apple trees are rooted deep in our folk tales and mythologies and have been around as long as the stones. The people who made Carnac would also have spent days like this gathering semi-wild crab apples and no doubt their homes were as full of the smell of apples cooking as was our farmhouse kitchen. Life goes on in and around the big, momentous events, much as it always has. A door into their world opened for me and I felt the connection to those long-ago ancestors in a full circle of shared humanity.

We do not need to know the how and why of the stones. The fact of their being is what is important. People like us co-operated to make something magnificent that has lasted for millennia not only here at Carnac but also at Stonehenge and Newgrange, at Brogdar and Callanish to name just the most famous ones. They built and they thrived and then they stopped; quite suddenly no more monuments were made. Their time was over. The people did not vanish, no doubt they went on collecting apples and making the Neolithic equivalent of jam but some deep change or trouble overtook their society and they no longer had the will or energy to build monuments. Maybe a plague reduced population numbers to the point where large scale co-operation was no longer possible.

Our society is also engulfed in trouble. Unlike our Neolithic ancestors whether or not it overwhelms us lies in our own hands. The plague we face is a deluge of lies, hate and abuse that is destroying the trust necessary for co-operation. I profoundly hope we have the will to cure our plague. The thread that connects our world view to our ancestors’ is the understanding that we are a social species who thrive best when we co-operate. There is an African proverb that sums up, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.”

For all its scary present troubles the world is a beautiful place. I look around and find joy and I try to share it with others through my art and my writing and my way of being.. This thread of connection is the antidote we need to the strident voices of division and hate that drop into our inboxes and poison our discourse (and remember art and jam-making are enduring and delightful shared activities).

centre: the apples

right: tree and stone

centre: the kiss

right: the fist

Return to Home